I take my dog, Diego, for a walk over my lunch break hoping some fresh air will do me good. I’m in my new uniform: torn Joe Fresh sweatpants shoved into muddy Tretorn boots, headphones crammed in my ears. A little boy and his mother walk towards us and as we get closer he points and says “doggie.” His mother asks if he can pet the dog and I have Diego sit so the boy can clumsily pat his back. I usually love these passing interactions. I love how Diego, not a real fan of being touched by anyone but my husband and me, is somehow able to sense when it’s a child and that he needs to suck it up and be a dog.

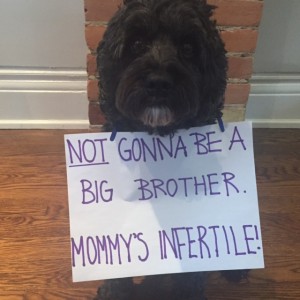

Usually I would tell the mother how cute her son is. I would kneel down and say to him “this is Diego and what’s your name?” Today, I want these lovely people to go away, to leave me and Diego alone. “Yeah, it’s a fucking doggie, genius,” I want to say. “Did you know I’m barren?” I want to say, looking the mother square in the eyes. All I can see is the little boy or girl I have hoped to have, how I dreamed of them petting Diego just like this and loving him as I do. This little boy is not mine and this is not his dog and I wish he would just go away.

After years of infertility treatments, I will no longer be trying to have a biological child. The hundreds of injections I’ve had, the hundreds of blood tests and transvaginal ultrasounds, the three times I have been put under to have my eggs extracted from my body, the months and months of nausea and bloating and weight gain and mood swings and headaches that I thought would never end (that go on for months after a failed cycle), the thousands and thousands in life savings we have spent, have all yielded nothing. We are no closer to having a child than when we began this process years ago. We are just older. And so very, very tired.

It’s not really the loss of my biology that feels so painful. I wish I could explain to you how very little the biological link means to me. I don’t need to see a little girl with curly hair and my husband’s bright, beautiful eyes. I don’t need to pull out my baby albums and compare. Of course that’s the baby I’ve imagined, as I’ve talked to the embryo I had hoped was nestling into my uternie lining. But only because they were the most obvious parameters. There is nothing really about me that is so essential, so absolutely amazing, that it must get passed on. Of course it would be fun to see the way my genes and my husband’s, who I love so much, arrange themselves together to form a whole new person. But what does this genetic constellation really matter when we’re talking about a whole new person, who will have his own hopes, dreams and challenges? His own life to live? What does it really mean to have your mother’s hair, the curls for which she is still searching for just the right anti-frizz product? It is not the genes I am grieving, but the peace. I am mourning the time and the pain and the hope that I will become a mother in the next 9 months. Or the 9 months after that. Or the 9 months after that. I am mourning the lost bit of living I feel like I have missed out on, as I have lain on the bathroom floor retching from all the hormones.

I have been crying a lot. I’ve cried in every room in my house. I’ve cried in the grocery story and at the coffee shop and at the library. I’ve cried in so many places that it’s almost become a game to me now, like a misery bingo, where I fill in all the squares of all the places I have cried.

My dear sister-in-law lost her father last year. I attend his unveiling and hold onto my own father and cry. I feel myself breaking down, feeling the pain of my sister-in-law’s loss. We sing “Sunrise Sunset,” one of her father’s favourite songs, and by the end of all of us singing together, I am no longer crying for her or her family but for me, and this makes me cry even more. Who will bury me, I think? I don’t care about being remembered after I am gone. I’m concerned about the actual logistics of it. Who will actually make the call to say that I’ve succumbed? My nine year old niece asks me to lay a rock on the headstone with her, as is Jewish custom, and I want to kneel down beside her right there in the cemetary and get this finalized. I squeeze her hand and she squeezes back and I hope she understands what I’m trying to say: that I’m sorry she might be the one to have to call the funeral home.

I walk Diego some more, back and forth along the same routes. I listen to Ta-Nehisi Coates read his latest book, Between The World and Me, and it is so stirring and so charged and so painful and so moving and I can’t stop crying. I listen to Ta-Nehisi describe his son’s tears, on hearing Michael Brown’s killer would not be indicted, and I can’t handle the injustice and unfairness of it all. The world is so fucking unfair. And in the face of such incredible and important work on the crisis in America, listening to the harrowing details of the outrageous inequality Ta-Nehisi has lived and Ta-Nehisi has seen, I think about the fact that the book is written as a letter to his adolescent son and how lucky he is to have a son (a beautiful son!), to write to in this painful, unjust world. The way Ta-Nehisi describes it, his love for his son sounds like a beacon of salvation and I want so very much to be saved.

“But you have a son, Ta-Nehisi,” I want to cry, my heart contracting in pain. “You have a son you say is your God and doesn’t that mean everything?! You have a son to bury you!” I am so ashamed by this thought that I stop, jerking Diego to a halt as I bend over with my hands on my knees, feeling as though I might throw up by the side of the road. This is all so not the point. It is the very opposite of the point, as he describes how he has grown up afraid for his body and now afraid for his son and his son’s body. Shouldn’t I be worrying about the world at large and the bigger injustices plaguing the people already here and not just my own small misfortune? Isn’t it an obscene reaction to his words, to turn privilege into the distinction between fertile and barren? I am sickened by this pinprick of jealousy I feel over Ta-Nehisi’s son, and of all the pinpricks of jealousy I have ever felt: when a mother asks if her child can pet my dog, when I see vacation pictures of happy families together on sunny beaches, wishing so much that my life was a little easier, a little more straightforward. A little happier. A little sunnier. My envy, my self-absorption, feel so petty and so very, very, childish and I am terrified what my continued barrenness will do to me – how it will keep halving and distorting and halving again my world view, until I can only see the vastness of the universe through a pinhole, unable to feel anything but my own pain.

If you haven’t already, check out the trailer for my new web-series about infertility. It is much funnier than this post! https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=sLqSlmok9KA

![Letting Go of Biological Motherhood I take my dog, Diego, for a walk over my lunch break hoping some fresh air will do me good. I’m in my new uniform: torn Joe Fresh sweatpants shoved […]](http://sadinthecity.com/wp-content/uploads/2016/03/fertilifucked2-576x250.png)

![Am I Doing Everything Right to Become a Mother This month for fertilty matters, I wonder if I’ve done everything right to become a mother or if I drank too much coffee. You can check out my post here: […]](http://sadinthecity.com/wp-content/uploads/2015/07/IMG_05621-100x100.jpg)

![Writing for Fertility Matters – Smile Though You’re Infertile I am honoured to be contributing to Fertility Matters, a national organization that empowers Canadians to help reach their reproductive health goals by providing support, awareness, information and education; and […]](http://sadinthecity.com/wp-content/uploads/2016/06/StephenWendyDiego-100x100.jpg)

![Letting Go of Biological Motherhood I take my dog, Diego, for a walk over my lunch break hoping some fresh air will do me good. I’m in my new uniform: torn Joe Fresh sweatpants shoved […]](http://sadinthecity.com/wp-content/uploads/2016/03/fertilifucked2-100x100.png)

![I’m Expecting….A Web Series! I am so excited to share with you that I’m expecting…. a web series! Here is the trailer for How To Buy A Baby: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=sLqSlmok9KA My team and I are […]](http://sadinthecity.com/wp-content/uploads/2016/03/prego-announcement-100x100.jpg)

![I am a Grown-Up! Even if my Nieces Don’t Think So… I begin to suspect my nieces, 12 and 9, don’t quite see me as a grown-up when I get a text from one while she is playing at the park […]](http://sadinthecity.com/wp-content/uploads/2015/10/aunt-big-deal-100x100.jpg)

![The Dialogue Project I am honoured to have contributed a piece to the Dialogue Project, a social mission dedicated to raising funds and awareness about mental illness. You can check out my post […]](http://sadinthecity.com/wp-content/uploads/2015/10/dialougeproject-100x100.png)

Wendy,

This is so beautiful in its exquisite clarity and pain. Every time I read something you write I feel a little jealous of how you can make your world, even in pain, so relatable, so universal. And then I’m grateful for it. Sending out love. Love, and hugs, and gratitude.

xoxo

Rachel

Thank you so much for your kindness, Rachel! I am definitely not someone to be jealous of. I so appreciate you taking the time to write and share your sweetness and love. Wishing you all the best always!

Hi Wendy, I’m speechless. I feel like one of Job’s friends, useless, but just want to send you a cyber hug and say thank you for sharing your journey. Who knows how many others will be comforted in the knowledge they are not alone and that someone else truely understands their heartache and sorrow.

Strangely: Right before I opened your email this morning I had been reading the stories of Sarai/Sarah, and Rebekah, (I’m remembering Hannah now too) and I was thinking how awful it must have been for them. Still mulling I closed the Book, opened my iPad, and hit Mail! Yours was the first email I opened… You are not forgotten. Love and hugs, Elizabeth

Thank you so much for your kindness Elizabeth and for reminding me of the strong women before me. I hope my story ends like Sarah’s and Hannah’s. Less so, Rebekah! Thank you for taking the time to write and I am wrapping myself up in your cyber hug and sending one back to you.

Wow, Elizabeth summed it up very well: “I feel like one of Job’s friends.”

Thank you for your eloquence in sharing your pain.

It will make me think twice before making assumptions.

Thank you so much for your support Victoria. So kind of you to write. Wishing you all the best always.

YMMD with that answre! TX

I've had reactions like this to skincare aimed at clearing spots and I think it's probably the salicylic acid in them that dries the skin so much. I avoid it at all costs now. I swear by Neals Yard Palmarosa face wash for bad skin days. xxx

Love all the stitching, but Mailart is one of my favorites! Well, that and fobs, too…lol Glad you don't need surgery and hope you can deal with it easily.

I hope it’s not too weird that I felt a need to send my love and support even though I am a stranger.

I stumbled on this blog, posted by a friend who is going through a lot of the same things you are. It’s so unfair and I am so, so sorry. You are a beautiful, honest writer. Not petty. Not bitter. Not self-absorbed. Just sad.

Wishing you so much happiness. xxxx

It’s wonderful that you wrote! Thank you so much for taking the time Sheri! I so appreciate your characterization as sad as opposed to bitter. That helped so much. Sending so much love and happiness back to you!

It’s been years since I’ve commented on an infertility blog, but you’ve called me out of retirement!

Trying figure out for yourself, much less explain to anyone else, why the loss of the genetic tie is…a loss, seems to be so difficult. There are lots of parts that have held true for me along the way, today “it’s the peace I am grieving.” I so get that. When people, sorry people, have said to me “it all turned out fine in the end!”, I’ve always claimed the disruption and trauma of the constant interruption and unfolding, not to mention the vag camming. (((((((Hugs and solidarity)))))))

I remember in the throw of a particularly bleak time I walked not a grocery store and it was overrun by mothers and babies. And then it dawned on me that everyone in that grocery store was somebody’s baby! All of these people, even 80 year olds, were someone’s baby, and that meant EVERYONE could get pregnant and have a baby, except me. As you can imagine, I fled and picked up burritos for dinner.

This is an awful, awful place, and the exits are all marked, but each has a nearly Carrollesque set requirements to fulfill.

((((((Love)))))) and strength and comfort to you.

Thank you so much for coming out of retirement for me Sarah! And thank you for your hugs and solidatrity. I can so relate to your moment in the grocery store – you describe it so perfectly and painfully and I am sorry you had to go through it. Good call with the burritos – at least I know what I’m going to have for dinner tonight now!

Here from Mel’s round-up. And leaving a comment, though I will likely be clumsy at it. Today marks 4 yrs since my second miscarriage, which was basically the one that broke me. All you describe with the emotions and thoughts I’ve had and still have. I’m not about to tell you that there will be happiness at the end of your journey or offer advice on how to fix any of this. What I will say is yes, it’s fucking unfair. The world is absolutely unfair. And I’m sorry for that. Sorry that after all the treatments and sacrifices you are facing these questions and grieving the loss of something so dear.

I wish I had answers. But to answer your questions and help guide you forward. What I can do is validate all you’re going through and let you know that you are not alone. And that 4 yrs later, when we stop to pet the dogs in the park, I do look into the eyes of the owner, looking for hints that they know this pain. And that it’s still with me too.

Not the least bit clumsy, Cristy, but beautiful and heartbreaking. I am so very, very sorry to hear about your miscarriages and understand feeling like it broke you – but then I read your words which are so strong and so courageous and so real and I think nothing could break you and that gives me hope that maybe while I feel so very broken I am not as broken as I feel. You are clearly an incredible person. Thank you for your words and for taking the time to write. I wish I had answers or that I could heal your pain too. If I could, I would.

I’m here from Mel’s Round-Up too. Your last sentence spoke to me. You’re allowed to feel your pain, your loss – of time, of your future, of your innocence – without comparing it to others. Your grief is real, not petty or childish, but deep and complex and raw. It won’t always feel like this, I promise. I’ve been where you are, but I’m not any longer. But when you’re in the midst of it, it’s hard and lonely and there never seems to be a way out.

Right now, don’t beat yourself up for feeling the way you feel. You’ve been through, and you’re going through, too much already.

I needed to hear this so much Mali. Thank you for taking the time to write it. I needed to hear that it’s okay to be sad right now but that it won’t always feel that way. I read this quote today by Zita West that sayd “Just because it’s not now, doesn’t mean it won’t ever be” and it helped and I thought the reverse must be true too: “Just because it is now, doesn’t mean it will always be.” Thank you so much for your kindness.

I know how you feel, girl. I used to walk my dog every day through the park and sometimes there would be busloads of kids going to the aquarium. One day, after our 3rd and final kick the IVF can – I went for our usual walk and of course, the kids were just getting off the bus and heading straight across our path. My restorative nature walk was ruined and my heart just broke. I thought about all I had lost – my innocence, my trust, my faith, even my marriage was damaged. Everything about what I had assumed about my womanhood was different. I did go on to adopt a child and I don’t mean to imply that is a choice for you because it did not resolve my infertility and all the feelings that come with it. You are not alone and things do get better. Infertility is a gift that just keeps on giving however…..

I’m so happy to hear that you did go on to adopt deathstar! Though I understand that adoption doesn’t cure infertility, it does give me hope that I might get to be a mother still and that as you say things will get better. I can imagine that there is a part of the grief though that is in your heart forever and I am so sorry you are carrying that with you too. Your adopted child, though, is so lucky to have such a caring and thoughtful mother.

Hey funny lady (although you’re right, this wasn’t web series trailer funny),

I can tell you that although I am child-free by choice, I have experienced much sadness and pain that comes with loss. I wasn’t going to be someone’s mother and, like you said, it’s not about inheriting genes. It’s not like seeing a little person getting my kick-ass thighs. And I have watched many scenes with children and cried knowing that I will never have that. What some people don’t understand is, even though this is my ‘choice’, it doesn’t mean that, for me anyway, it’s not any less of a loss. I hope that makes sense.

I also want to tell you that being the Girlfriend Mom, allowed me to see what I had been missing but also what I will continue to miss. I had the opportunity to love someone else’s little people -something that I never thought I would be able to do and, well, love is love, bio or not. And lately I have been crying, intermittently, over who’s going to make my funeral arrangements. It’s a weird thing to think about and it’s all a mess and complicated but you have the beautiful talent of being able to work it, through your writing. Oh, my god, this whole comment was so not funny. Let’s get back to the funny!!! xoxox

Hey Funny Lady, thank you so much for sharing your story. I always appreciate your humor and honesty and insight. You know that movie plot line with besties who say they’ll marry each other if they’re still not with anyone by the time they’re 30? Let’s make a dying pact! Whoever dies second will bury the other one! It’s a romantic comedy but super dark and both heroines die at the end. Whaddaya say!?!?! Wanna be my burial bestie!?!?!

home https://hotevershop.com/mans-health/maral-gel/

go to my site https://lightflying.space/cat-from-fungus/psolixir-cream/

more information https://naturalmedstore.space/bgr/beauty/bioretin/

click over here now anita blond nude

y7ate1