The last time I went skiing, Jessica Rabbit was a hot sex symbol, Tiffany thought we were alone now, and I bore an uncomfortable resemblance to my Cabbage Patch Kid, Gabriella Something Or Other.

My dad used to take my brothers and I on these amazing ski trips over winter break, twice to Vermont and once to Lake Placid.

Each week-long trip was filled with big mountains, powdery snow, and hot chocolate with sizable marshmallows.

I didn’t actually know how to ski but I refused to take a lesson, despite my dad’s insistence. My brothers and I were loyal fans of High Mountain Rangers-a television show about a highly trained search and rescue ski team in the Tahoe mountains. I watched the Rangers search the wilderness for people injured in unexpected avalanches, typically fighting through blizzard conditions to reach them, without even ruffling their long, side-swept 80’s hair; so I was certain that I would have no problem in temperate conditions on clearly marked ski slopes. I was right. I didn’t have any problems the first year, the second year or even the third, until the very last run of the very last day when I broke my tibia straight across. Except, we didn’t even know I suffered a fracture until 48 hours later when my family finally believed me when I said, “I think my leg is broken.” The hospital agreed.

Even though Health Central describes such a tibial fracture as a “traumatic injury,” skiing beside my dad and my two big brothers was one of the best times I ever had. I’m not sure what that says about my childhood, though, that my happiest memory involves a broken bone.

I had no trouble hopping onto skis and following my brothers down the steepest runs, without so much as a demonstration, because I was fearless back then. It wasn’t that I believed in my natural ability as a skiier. Rather, I thought I could engineer any circumstance by the sheer force of my unbridled desire and my unflinching spunkiness. I maintained the only thing standing between me and my potential was the courage to pursue it. When I stood at the top of those slopes, I hadn’t yet failed. I hadn’t lost people I loved and my anxiety didn’t have a name with a capital letter. Back then, the universe had yet to disappoint me. I had yet to disappoint myself.

My fall that day didn’t just break my leg. It also broke some of my confidence. This hesitancy didn’t just grow with me, but outstripped me. Somehow, I stopped seeing myself as the High Mountain Ranger and started seeing myself as the person caught in the avalanche. I would never accept rescue from another person and I didn’t trust my ability to dig my way out. So I never went skiing again. I ignored the coaxing of my dad, brothers and husband. I was terrified to go anywhere near skis and felt nauseous even watching the Olympians doing it, tensing up in anticipation of a possible fall. I didn’t want to fall again.

But now, 22 years later, in Ellicottville, NY with my family, the campaign to get me skiing began anew. My brother’s two girls, seven and five, had been taking lessons and were eager for me to join them. Despite my terror, they remained insistent, escalating the sweetness of their eyes and the poutiness of their lips. I wanted to be “bold and adventurous Aunty Wendy,” not “afraid-to-go-skiing Aunty Wendy,” so I finally relented. But my nerves did not. I sat with my head between my knees on the car ride to the mountain, my long johns damp with sweat. After being commandeered out of the washroom and onto the chairlift, I was overwhelmed with panic. My legs began to shake as the tips of my skiis chattered against each other. My dad had to physically push me off the lift as I held on hoping to take it back around to safety.

As promised, my nieces began to show me what to do. Each of them eased themselves onto the slope and quickly gained speed. I didn’t notice anyone else as they made perfect S’s across the mountain, moving boldly from side to side. I could only see them from behind but felt certain they were smiling. I was in complete awe of their assuredness. They were daring and dazzling, undaunted by the ice or the other skiiers. Watching them for a moment, I had a glimpse of my former self when I was young. I saw that fearless little girl with nothing holding her back.

What happened to me? What happened to my spirit?

I felt a certain resignation take over. I took a deep breath, pushed off and headed straight down. I let the momentum propel me forward all the way to the bottom of the run where my family cheered. They encircled me, congratulating me on conquering my fear. They applauded me for not backing down in the face of my panic and they shared their pride in me. I was so happy I did it. I was so excited to watch my nieces and so relieved that I didn’t disappoint them.

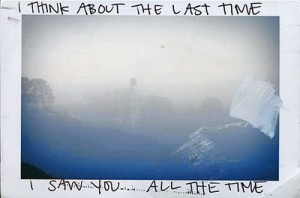

But the truth is, I didn’t really overcome my fear that day. I didn’t master my terror, take it by the hands and leave it at the top of the slope. What I couldn’t tell them, what I can never tell them, is that standing there at the top of the mountain, looking out as far as I could, I realized that this time I didn’t care. I didn’t care if I broke my leg. I didn’t care if I fell off the edge. I didn’t care about anything.

![Am I Doing Everything Right to Become a Mother This month for fertilty matters, I wonder if I’ve done everything right to become a mother or if I drank too much coffee. You can check out my post here: […]](http://sadinthecity.com/wp-content/uploads/2015/07/IMG_05621-100x100.jpg)

![Writing for Fertility Matters – Smile Though You’re Infertile I am honoured to be contributing to Fertility Matters, a national organization that empowers Canadians to help reach their reproductive health goals by providing support, awareness, information and education; and […]](http://sadinthecity.com/wp-content/uploads/2016/06/StephenWendyDiego-100x100.jpg)

![Letting Go of Biological Motherhood I take my dog, Diego, for a walk over my lunch break hoping some fresh air will do me good. I’m in my new uniform: torn Joe Fresh sweatpants shoved […]](http://sadinthecity.com/wp-content/uploads/2016/03/fertilifucked2-100x100.png)

![I’m Expecting….A Web Series! I am so excited to share with you that I’m expecting…. a web series! Here is the trailer for How To Buy A Baby: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=sLqSlmok9KA My team and I are […]](http://sadinthecity.com/wp-content/uploads/2016/03/prego-announcement-100x100.jpg)

![I am a Grown-Up! Even if my Nieces Don’t Think So… I begin to suspect my nieces, 12 and 9, don’t quite see me as a grown-up when I get a text from one while she is playing at the park […]](http://sadinthecity.com/wp-content/uploads/2015/10/aunt-big-deal-100x100.jpg)

![The Dialogue Project I am honoured to have contributed a piece to the Dialogue Project, a social mission dedicated to raising funds and awareness about mental illness. You can check out my post […]](http://sadinthecity.com/wp-content/uploads/2015/10/dialougeproject-100x100.png)

Powerful and painful punch!!!

I can’t ski. I gave up after crashing into the instructor and knocking him over on my third lesson. As for those ski lifts…….treacherous, I avoid them!

A.

I like that strategy. Good thing there’s always hot chocolate in the chalet!